Oct 2024: Lawrence Alma-Tadema and the nineteenth-century 'period eye'

New issue: Oud Holland 137 (2024) 3

15 October 2024

This month Oud Holland opens its pages with a striking technical analysis and reconstruction of the cup of Veere – an exceptional fire-gilded silver ornamental piece from circa 1547-1548. Hanne Schonkeren now offers a new perspective on the circumstances of its creation in Antwerp, and identifies the anonymous Master with the lion head in a shield as the artist.

With Pieter Pourbus' quintessential Last Supper of 1548 as a starting point, Bram de Klerck discusses the iconography of the theme in the context of Medieval and Renaissance imagery. Notably, the figure of Judas plays a pivotal role in some of these paintings and, conspicuously enough, also in the viewer’s personal experience of participation in the biblical story.

Finally, through a detailed analysis in conjunction with contemporary reviews, Joan Mut i Arbós reconstructs the late-nineteenth-century perspective on Alma-Tadema's work. The question he poses is how Alma-Tadema's contemporaries would have seen his work. With access to classical sources available at the time, two of his key paintings suddenly become social critiques of the wealthy class.

The editors of Oud Holland wish you an inspiring Fall.

Hanne Schonkeren – Master with the lion head in a shield: A new attribution of the ornamental cup of Veere (c. 1547-1548) – pp. 85-106

SUMMARY

The city hall of Veere, in the Dutch province of Zeeland, preserves an extraordinary fire-gilded silver ornamental cup on foot. This precious object, depicting Maximilian of Egmont (1509-1548) crossing the river Rhine and arriving with his troops in Ingolstadt, was made circa 1547-1548 to commemorate the Battle of Mühlberg (1547) and to honor Maximilian's pivotal role in the victory. His cousin Maximilian of Burgundy (1514-1558) inherited the cup in 1548, and, in turn, donated it to the city of Veere. The cup's ceremonial status continued through the centuries and is presented to the Dutch monarchs during official city visits to this day. Yet, despite its cultural significance, the place of production, atelier, and particular silversmith has long been a topic of debate. Notably, the cup of Veere lacks hallmarks – a quality label for the technical skills and the correct alloy, which indicates a date, provenance, and master. Neither is the piece mentioned in any known archival records.

Therefore, previous scholarly attributions of the cup to a specific city, atelier, or maker, relied mostly on stylistic features. This article, however, examines the making process and techniques used, revealed by the dismantling of the piece in 2018. Detailed technical examination of cast elements and chased decoration have uncovered the signature moves of the maker. The stem of the cup is adorned with cast lion heads and is composed of a chased fruit basket. Identical elements are identified in the so-called Founders' cup (Emmanuel College, University of Cambridge), which bears the Antwerp hallmark of the years 1541-1542 and a master stamp depicting a lion’s head in a shield.

Comparative analysis and up-close visual inspection offer a new perspective on the making process of the cup of Veere, proposing Antwerp as its production place, and assigning the anonymous Master with the lion head in a shield as the maker of the cup. In putting forward this case study of early modern gold and silverware, it also demonstrates the key role that research on craftsmanship and technique may play in reaching definitive conclusions regarding the origin of significant objects.

Bram de Klerck – Trading places with the traitor: Pieter Pourbus (c. 1523-1584) and sixteenth-century Last Supper iconography – pp. 107-120

SUMMARY [download article]

Pieter Pourbus' Last Supper of 1548 (Bruges, Groeningemuseum) contains some unusual iconographic elements that have not yet been extensively analysed: the figure of Judas, rising from the table and making a move to leave the gathering; the devilish creature entering the room from the right; the boy picking up the overturned chair in the foreground. By making use of recent scholarly insights into the employment of the anthropological concept of 'liminality' in the context of the visual arts (notably by Lynn Jacobs on Early and Renaissance Netherlandish painting and manuscript illumination), this contribution aims to show that these features were meant to enhance the contemporary viewer's involvement in the depiction. The work seems to invite them to enter, as it were, the painted realm and to take Judas' abandoned place.

An investigation of Last Supper imagery in the Western European visual arts from the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance reveals that in some cases the figure of Judas plays a distinctive role in the presentation of the iconography and in the viewer's devotional and psychological experience of participation in the sacred story. Sometimes, as in a panel from the circle of the Master of the Amsterdam Death of the Virgin (c. 1485-1500) or in the likewise anonymous Antwerp Last Supper (c. 1525-1530), a mortal human has been included in the painting, portrayed in the immediate vicinity of the scene and apparently being ready and prepared to take over Judas' place once the latter leaves the gathering. Pieter Pourbus' painting, which probably played a role in the literary-religious context of the Bruges rederijkers' Chamber of the Holy Spirit, is more inventive in nature. Lacking an intermediary worshipper depicted in the foreground, it transfers this worshipper’s role to the viewer, thus establishing a bridge between the painted realm and the real world.

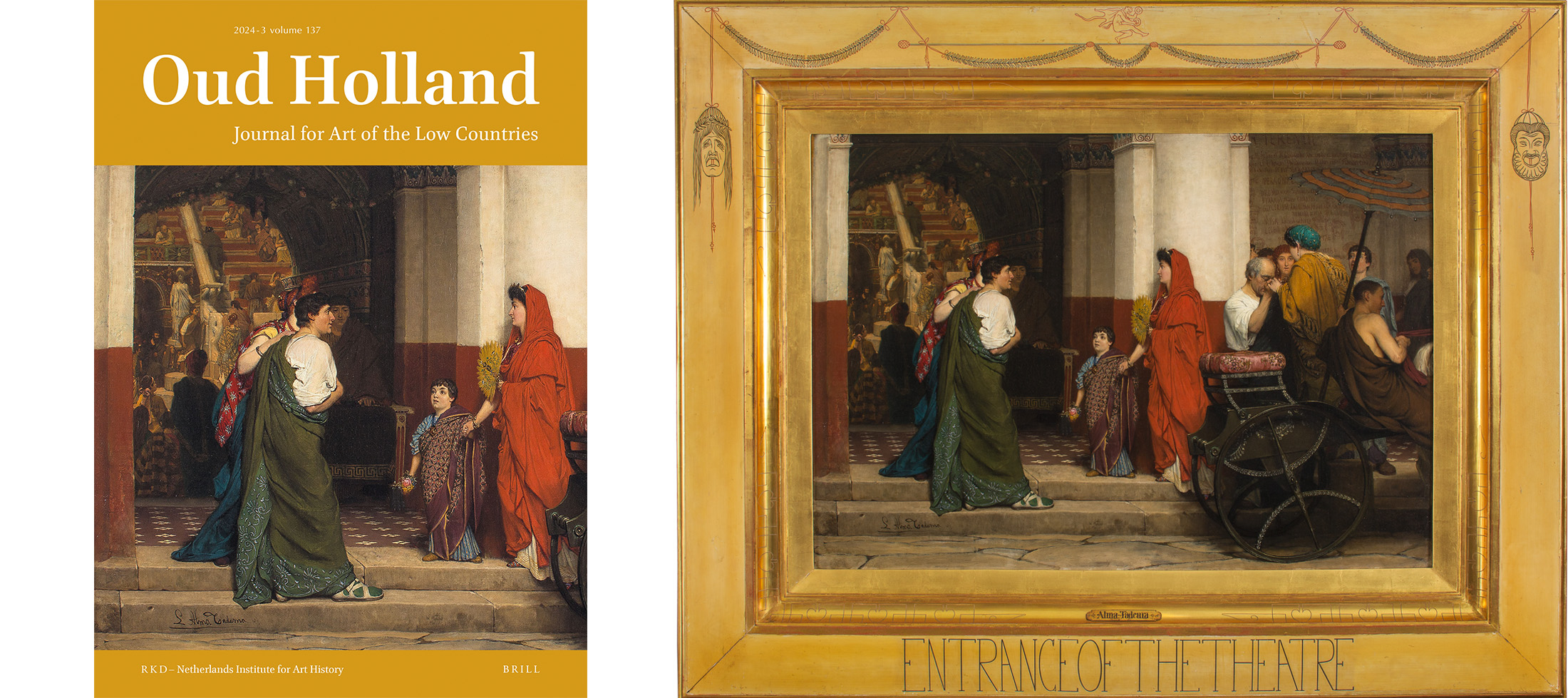

Joan Mut i Arbós – Lawrence Alma-Tadema and the nineteenth-century 'period eye': Classical sources for his Entrance of the theatre (1866) and An exedra (1869) – pp. 121-139

SUMMARY

The Anglo-Dutch artist Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1836-1912) is known for being one of the leading representatives of historical genre painting. His paintings are often set in antiquity that usually transmit a peaceful atmosphere, although they also regularly refer to classical sources that include critical messages. Two key works of Alma-Tadema's Pompeian period are Entrance of the theatre (1866) and An exedra (1869). These works are paradigmatic of the artist's in-depth knowledge of classical civilization. He seemed obsessed with the historical accuracy of his paintings, which can be partly explained by the fact that general education at the time was steeped in the classics, and the public’s appreciation of his paintings must have been directly related to what was taught at school.

Through a detailed analysis in conjunction with contemporary critical reviews, the author intends to reconstruct the late-nineteenth-century perspective on Alma-Tadema's work. The question is how his contemporaries may have viewed his paintings, and how the concept of the 'period eye', developed by Baxandall, can be of use. It turns out that, with access to these classical sources, Entrance of the theatre becomes a scathing critique of the vanity and conceit of the wealthy class. Alma-Tadema’s reference to Terence's comedy Andria convincingly complements a social criticism depicted through a public scene at the entrance of the Small Theatre in Pompeii.

Additionally, the inscriptions and monuments that were associated with the famous family of the Holconians in particular, and theatrical patronage in Pompeii in general, must have been of particular interest to Alma-Tadema. This also emerged in An exedra, a scene around a tomb at the Via dei Sepolcri in Pompeii. The result is an image that, beyond a casual daily image from antiquity, also aims to show social injustice through the lost gaze of the enslaved person.

These paintings show how Lawrence Alma-Tadema was capable of making numerous references, by layering several meanings and suggestions taken from antiquity. They also constitute a clear example of how he used and combined all his knowledge of classical architecture and fashion available at the time, to elaborate a pictorial narrative that pointed to the core of historical reconstruction.