Jan 2020: New issue Oud Holland 132-4

New issue: Oud Holland 132-4

28 Jan 2020

This issue of Oud Holland presents four fifteenth and sixteenth-century topics. The very detailed scenes from the passion of Christ by Hans Memling show a particular sculpture group which now, for the first time, is explained in the context of the complete work. Virtual pilgrimage – discussed in the second article – was a fascinating alternative for Catholic people who were not able to leave their homes for a religious journey to Rome. A recently rediscovered panel with the image of Christ on the cross offers important insights into this practice around 1500.

The famous sixteenth-century artist Maarten van Heemskerck must have been constantly searching for artistic motifs in a quest to create his own distinctive style. This in-depth article shows not only this practice of emulation and innovation, but also presents new work by Heemskerck. Lastly, a recently acquired glass panel by Wouter Crabeth triggers the author to revisit the whole series of painted windows of the Sint-Janskerk in Gouda. Apparently, the window panel – with a skeleton, a devil and a personification of sin – is not a straightforward representation. See below for the summaries of each article.

Marjan Pantjes – Uncovering the identities of Cain and Lamech: Christian typology in Hans Memling’s scenes from the passion of Christ (ca. 1470) – pp. 149-158

SUMMARY

Hans Memling’s panel with the Scenes from the passion of Christ of circa 1470 (currently in the Sabauda Gallery in Turin) shows three grisaille sculpture groups. One of them – in the architectural frame above the scene of the flagellation of Christ – consists of two nude men, each carrying an attribute. In this article they are identified as Cain and Lamech. These Old Testament figures are typologically connected to the passion of Christ in general and the flagellation of Christ in particular. They can be identified by their weapons, respectively a jawbone and a bow and arrow. The former was used by Cain to slay his brother Abel and the latter was used by Lamech to kill his ancestor Cain. Both figures have rich exegetical and pictorial traditions, which will be touched upon to explain their prominent placement in Memling’s painting.

Miyako Sugiyama – Performing virtual pilgrimage to Rome: A rediscovered Christ crucified from a series of three panel paintings (ca. 1500) – pp. 159-170

SUMMARY

Pilgrimage is one of the most indispensable aspects to consider when determining the function of late medieval imagery, especially images that are related to indulgences. Some of them have been examined as an aid to perform pilgrimage without the hardship of an actual journey – a virtual pilgrimage – through which one could earn indulgences. Prominent examples are the small panels with Saint John the Baptist with a letter ‘A’ in Museum Catharijneconvent in Utrecht, and the Virgin and Child with a letter ‘D’ in the Bob Jones University Museum and Gallery in Greenville. The first was thoroughly examined in 1981 by Henri Defoer, who compared the panel with an illustration of Die costelijke scat der gheestelijker rijcdoem (Heavenly treasure of spiritual wealth), which was a pilgrimage guide to Rome, especially to the Seven Pilgrimage Churches in Rome. On the basis of the subject and its letter, Defoer concluded that the panel shows San Giovanni in Laterano. The second was reported by Catherine Reynolds in 1997 as a panel with Santa Maria Maggiore.

This article presents for the first time a third panel, that was recently rediscovered in a private collection. The panel depicts a Christ crucified in front of an unknown church with a letter ‘G’. After summarizing Defoer’s study on the Utrecht and Greenville panels, the author will present the panel as Santa Croce in Gerusalemme, the last station to perform the virtual pilgrimage to Rome. The discussion will be followed by stylistic analysis to suggest that the three panels were made by different members from the same workshop in the early-sixteenth Southern Netherlands.

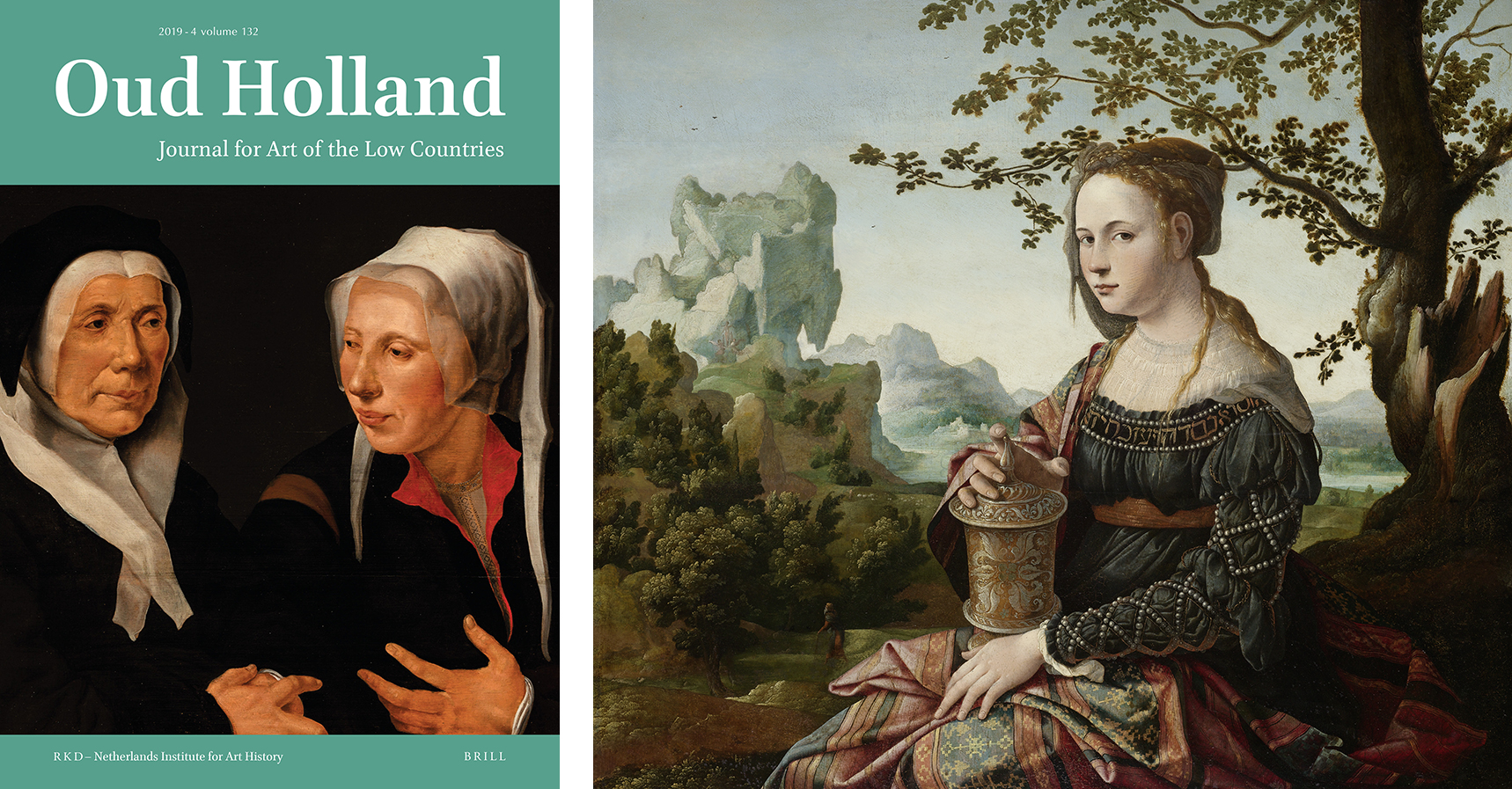

Ilja M. Veldman – Adaptation, emulation and innovation: Scorel, Gossaert and other artists as a source of inspiration for the young Heemskerck – pp. 171-208

SUMMARY

In the past, most works by Maarten van Heemskerck produced before his departure for Rome in 1532, were credited to Jan van Scorel, including paintings that are now recognised as Heemskerck’s most outstanding works. In this article, the author identifies one of these paintings, the Rotterdam Schoolboy (1531), as the Alkmaar youth Bartholomeus van Teijlingen. Heemskerck joined in 1527-30 Jan van Scorel’s Haarlem workshop and the influence of Scorel’s compositions is obvious.

The article also discusses the impact of other contemporary painters that were essential for Heemskerck’s early development. Stylistic characteristics of several of these paintings – the robustly sculptural figure style, dramatic luminary contrasts and illusionism, and extraordinary accuracy in the depiction of texture and detail – are rather indebted to Jan Gossaert. Gossaert was probably also the incentive for Heemskerck’s journey to Rome, for both shared a fascination for antique sculpture, large nudes and mythological themes, expressed in their works made during and after their Roman sojourn. Moreover, a journey to Bruges and Antwerp was significant for Heemskerck’s education. There he had the opportunity to study Michelangelo’s Madonna and the works of Jan van Eyck, Joos van Cleve and Quinten Metsijs. Van Cleve’s type of Lamentation was adopted in several early and later lamentations. The composition of Metsijs’s Unequal lovers inspired both Heemskercks Judah and Thamar and an unique, newly discovered genre painting, Daughter taking leave of her mother, that is published here for the first time. The painter was also familiar with the production of the Amsterdam workshop of Jacob Cornelisz.

Heemskerck was gathering an abundance of artistic information in a quest to forge his own distinctive voice and style. While struggling to merge these various artistic examples into a painterly idiom of his own, he displayed throughout his early development a few key qualities that were uniquely his: a powerfully expressive presentation of form and idea, a singular creativity in the use of visual sources, and an overriding ambition to emulate and surpass these sources. This urge of emulation inspired him not only to reshape traditional themes, but also to introduce completely new inventions to the pictorial tradition of the North.

Zsuzsanna van Ruyven-Zeman – The Gouda windows revisited: An unexecuted design by Wouter Crabeth – pp. 209-227

SUMMARY

At the end of 2018 Museum Gouda purchased a small glass panel, The resurrected Christ triumphing over death and the devil. It was attributed to Wouter Pietersz. Crabeth (ca. 1520/1530-1589), the glass painter from Gouda. Together with his younger brother Dirck (ca. 1510/20-1574) he executed the majority of the ‘Catholic’ windows of the Sint-Janskerk in Gouda. The glazing of this church, which was started in 1555 and completed in 1604 for the by then Protestant worshippers, is the most important surviving ensemble of Renaissance stained glass and matching cartoons in the Netherlands.

The extant oeuvre of Wouter Crabeth is smaller than that of Dirck. With the exception of his four documented Gouda windows and cartoons (1559-1566) and the glass medallion, all his drawings and glass panels are in foreign collections. Contrary to his other work, the newly acquired panel is not a straightforward representation of a scene from the Gospels. The customary sleeping soldiers in the foreground are replaced by a sitting skeleton, a reclining devil and a third person, whose headgear is inscribed with ‘zonde’ (sin). They are meant to represent the allegory of Christ triumphing over death, the devil and sin. A drawing in Dresden, first attributed to Dirck Crabeth and later to Lambert van Noort, shows striking similarities to the glass panel – both in iconography and style. It is also more complete, containing the figures of God the Father and two angels in the top section. The Dresden drawing, which is now attributed to Wouter Crabeth, is a design for a church window, of which the donor field is trimmed.

While similar allegories have formed part of both Catholic and reformist imagery, the presence of God the Father in the window design indicates the Catholic affiliation of the window’s intended public. It is argued now that this design was probably meant for the very last window of the choir ambulatory in the Sint-Janskerk, to be preceded by a crucifixion. Of the combined series of the lives of Jesus and his precursor John the Baptist, patron saint of the church, only the second came to full circle at the outbreak of the Dutch Revolt. In 1580 the two last empty windows were filled with panels – representing scenes from the passion of Christ – from the chapel of the redundant monastery of Regulars in Gouda, made in the workshop of Dirck Crabeth.