Sep 2020: Oud Holland presents a doctor from Delft with his family

New issue: Oud Holland 133 (2020) 2

18 September 2020

Technical and art-historical research on a group painting from 1635 in the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp has resulted in the discovery of the identity of the sitters. The first article reveals the outcome and presents the sitters as the Delft doctor Cornelis van der Heijde and his family.

The second article reconsiders the life and oeuvre of the remarkable artist Leendert van Beijeren (1619-1648). He appears to be an important pupil of Rembrandt, with his own style of monumental figures. However, he died already at the age of 29 years.

'Selling paintings to Sweden' discusses the contents of four unpublished letters by the painter Toussaint Gelton (ca. 1630-1680) to a Swedish count. This correspondence provides a rare insight into the relationship between a painter and his powerful patron.

The final article considers the WIC’s lavishly crafted gold box from 1749 within the framework of the Dutch-African gold trade in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It concludes that the discourse between haptic and optic sensory responses could have provoked conflicting narratives for the owner, Willem IV.

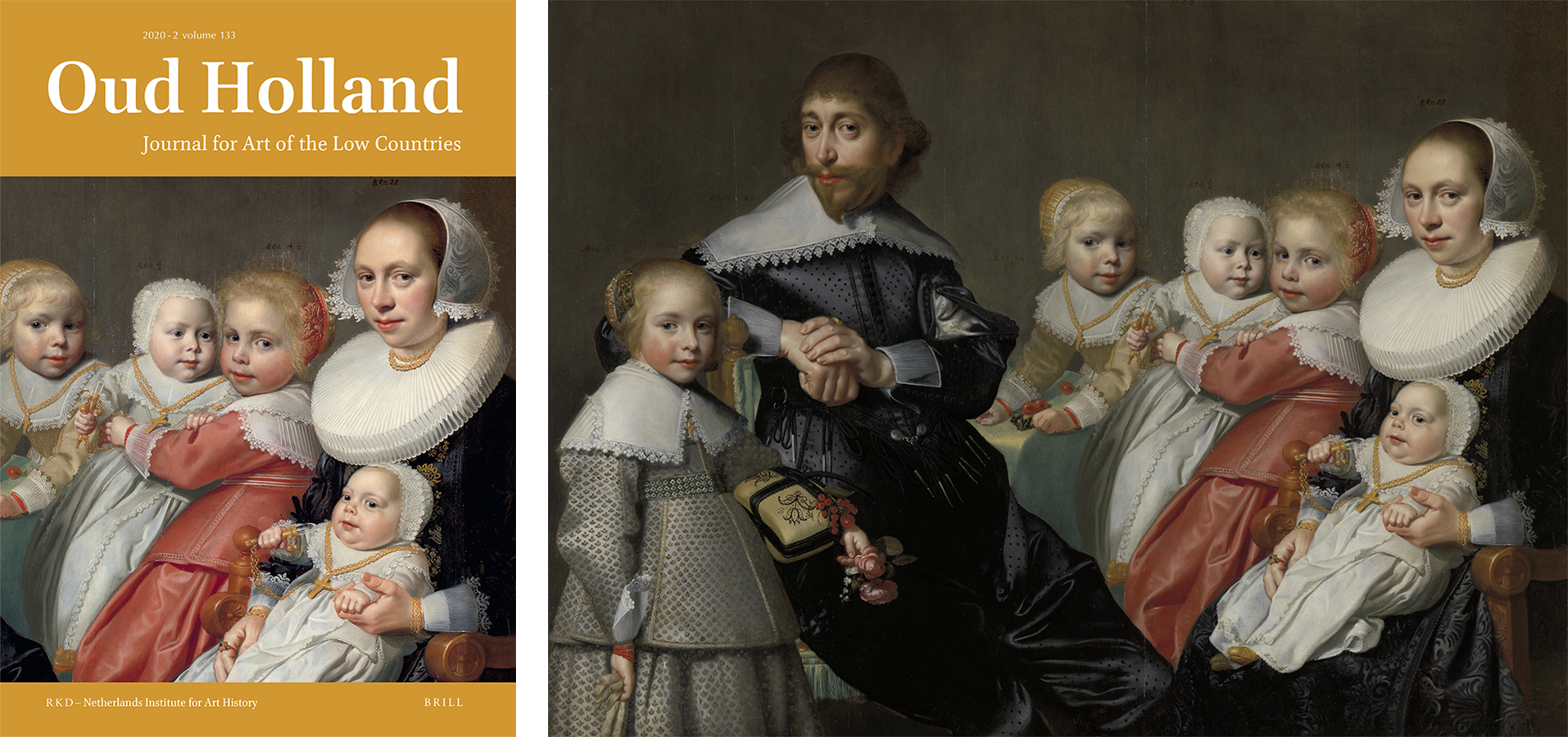

Frans Grijzenhout, Gwen Borms, Julia van Marissing & Sophia Thomassen – A Delft family portrait (1638) by Jan Daemen Cool – pp. 77-90

SUMMARY

Since 1935 the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp has held an unusually animated family portrait featuring a couple and their five children, including twins, which dates from 1638. The recent restoration of the painting has led to technical and art-historical research, with new insights into the history of the creation of this painting. This has resulted in the discovery of the identity of the sitters.

The painting was originally probably twenty centimetres wider on the right-hand side, but is otherwise still in good condition. On the basis of the provenance information, marriage and death certificates and notarial archives, it was possible to discover the family’s identity. The painting shows Cornelis van der Heijde (1601/2-1638), a Roman Catholic doctor from Delft, his wife Ariaentgen de Buijser (1610-1677) and their daughters – including twins – Aechken (d. 1652), Pieternelle (d. 1661), Digna (d. 1672), Anna (d. 1681) and an unknown child who died in 1639 (probably Adriaen or Ariaentgen). The painting was made only a few months after the birth of the twins, probably in the autumn of 1638. Cornelis van der Heijde died in November 1638. It is not clear whether his portrait was painted while he was still alive or made after an earlier portrait.

Rudi Ekkart convincingly attributed this family portrait to the Rotterdam painter Jan Daemen Cool (ca. 1589-1660). The form of the inscriptions and the characteristic rendering of the hands, eyes and mouths all support this attribution. It is true that Cool was trained in Delft by Michiel van Mierevelt, but until now we have known of no activities by him in that city after 1614. As far as we know, this is the only portrait that Cool made for a Catholic client. It forms an interesting pendant to the portrait of the likewise Catholic Van der Dussen family by Hendrick Cornelisz van Vliet of 1640 (Prinsenhof, Delft). In 1660 one of the portrayed sons, Cornelis, would go on to marry Digna van der Heijde, one of the daughters in the discussed family portrait by Jan Daemen Cool from 1638.

Jeroen Giltaij – Leendert van Beijeren (1619-1648): 'Disipel' van Rembrandt – pp. 91-107

SUMMARY

This article reconsiders the life and oeuvre of the unknown but remarkable artist Leendert van Beijeren (1619-1648), starting with a portrait that is now recognised as a self portrait by the artist. So far, this is the only signed work. Van Beijeren is mentioned as a pupil ('disipel') of Rembrandt in a document of 1637. This must have triggered Abraham Bredius and Nicolaas de Roever to publish all known documents about his work and life in Oud Holland in 1887. In 1915 Bredius also published, in his Künstler-Inventare, Leendert’s inventory of 1649.

Rembrandt had made some notes on the back of one of his drawings, dated from around 1636, which says that he had sold Leenderts a Flora for 5 guilders. Most probably the work was a painting that was sold to Leendert’s father Cornelis van Beijeren. The probate inventory of Cornelis from 1638 lists several copies after Rembrandt, which probably had been made by Leendert during his apprenticeship in Rembrandt’s studio. The inventory also mentions a large painting with the Sacrifice of Abraham and, again, a Flora, probably done by Leendert as well. Also listed is a "portrait of Leendert", which is likely the known Self-portrait. Additionally, this rich collection also contained a large amount of drawings and prints as well as a ‘passion book’ by Dürer, with a total value of 736 guilders, which Leendert received in 1644, when coming of age.

In 1647, Leendert made his will, while being ill. A year later, he was buried in de Nieuwe Kerk in Amsterdam. The inventory of his possessions were drawn up only in 1649: the room where he had lived stored several paintings, among which a large work with the Ecce homo made by Leendert van Beijeren himself, and a portrait of the artist, likely the signed self-portrait. Bredius identified the Ecce homo justly with the large painting in the Szépmüvészeti Múzeum in Budapest. Although neglected afterwards, Bredius also truly argued on stylistic grounds that both The parable of the workers in the vineyard (Städelsches Kunstinstitut), and The mocking of Christ (Hermitage) should be attributed to the artist. Leendert van Beijeren appears to be an important pupil of Rembrandt, with his own style of monumental and impressive figures. He died already at the age of 29 years.

Angela Jager – Selling paintings to Sweden: Toussaint Gelton’s correspondence with Pontus Fredrik de la Gardie – pp. 108-126

SUMMARY

This article discusses the contents of four unpublished letters by the painter Toussaint Gelton (ca. 1630-1680), to the Swedish count Pontus Fredrik de la Gardie (1630-1692). De la Gardie was a member of one of the most powerful and rich aristocratic families of Sweden; his brother Magnus Gabriel was married to the sister of Charles X Gustav. Members of the Swedish aristocracy had a keen interest in Dutch culture, and used the mediation of agents to access it. First contact between Gelton and De la Gardie was presumably established when Gelton visited the Swedish court to paint portraits of Charles X Gustav and his sister, in 1658.

Gelton sent De la Gardie a letter in 1665, from his workshop in Stockholm. Its contents demonstrate that the painter was also active as an art dealer. On his way to Amsterdam in 1667, Gelton passed through Hamburg, where he encountered a painting that was stolen from the count’s collection. In the letter, in which he informs De la Gardie of this, Gelton offers a painting by Frans van Mieris to a mutual contact, and later recommends that the court invite the portrait painter Cornelis Janson van Ceulen. In a third letter sent from Amsterdam in 1668, Gelton offers the service to send ‘anything’ the count desired from Amsterdam – suggesting a painting he attributed to Henri de Fromantiou. The fourth letter was sent in 1673, from Copenhagen, where Gelton had been assigned to paint a portrait of the newly installed Danish king, Christian V. Gelton worked as a painter at the Danish court until the end of his life. These four letters, therefore, provide rare insights into the relationship between a painter, and his powerful patron.

Carrie Anderson – Between optic and haptic: Tactility and trade in the Dutch West India Company’s gold box (1749) – pp. 127-143

SUMMARY

The object on which this essay focuses is a gold document box made by the Amsterdam goldsmiths Jean Saint and François Thuret and presented as a gift to Stadholder Willem IV by the Dutch West India Company (WIC) in 1749. On the lid of the box sits a large nugget of unrefined gold ore, around which are arranged three figures: an African man holding an elephant tusk; an African woman panning for gold; and Mercury, god of trade, who supports a cartouche containing the insignia of the WIC. To the right of the woman, figures extract gold from the earth, while on the left a European merchant holds a small bag of gold, with which he negotiates the purchase of enslaved people. The sides of the box picture the Dutch forts in Africa and Curaçao through which these commodities circulated, while the bottom of the box contains a map of West Africa, the coastline inlaid with gold. The high market value of gold – along with ivory and enslaved people – made the material composition of the box and the imagery on its surfaces a convincing assertion of the Company’s wealth.

This essay considers the WIC’s lavishly crafted gold box within the framework of the Dutch-African gold trade in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries as it was described in the travelogues by the Dutch authors and WIC employees, Pieter de Marees (in 1602) and Willem Bosman (in 1703). It argues that the emphasis the authors place on sight and touch as essential metrics for the measure of gold’s quality intersects with the visually stunning and conspicuously tactile qualities of Saint and Thuret’s box. Such an approach posits that registers of meaning were constructed through both iconographical and material interventions, which – in the case of the WIC’s gold box – manifests most emphatically in the differing compositional positions and tactile properties of Mercury and the two laboring African bodies over whom he presides. In the conclusion, the author suggests how this discourse between haptic and optic sensory responses could have provoked conflicting narratives for Willem IV when he held the box in his hands. The box’s imagery – although in dialogue with pervasive Eurocentric iconographies of the period – is simultaneously fraught with anxieties that reflect the WIC’s precarious position on the African coast in the first half of the eighteenth century.