Sep 2021: Latest double issue Oud Holland

New issue: Oud Holland 134 (2021) 2/3

7 September 2021

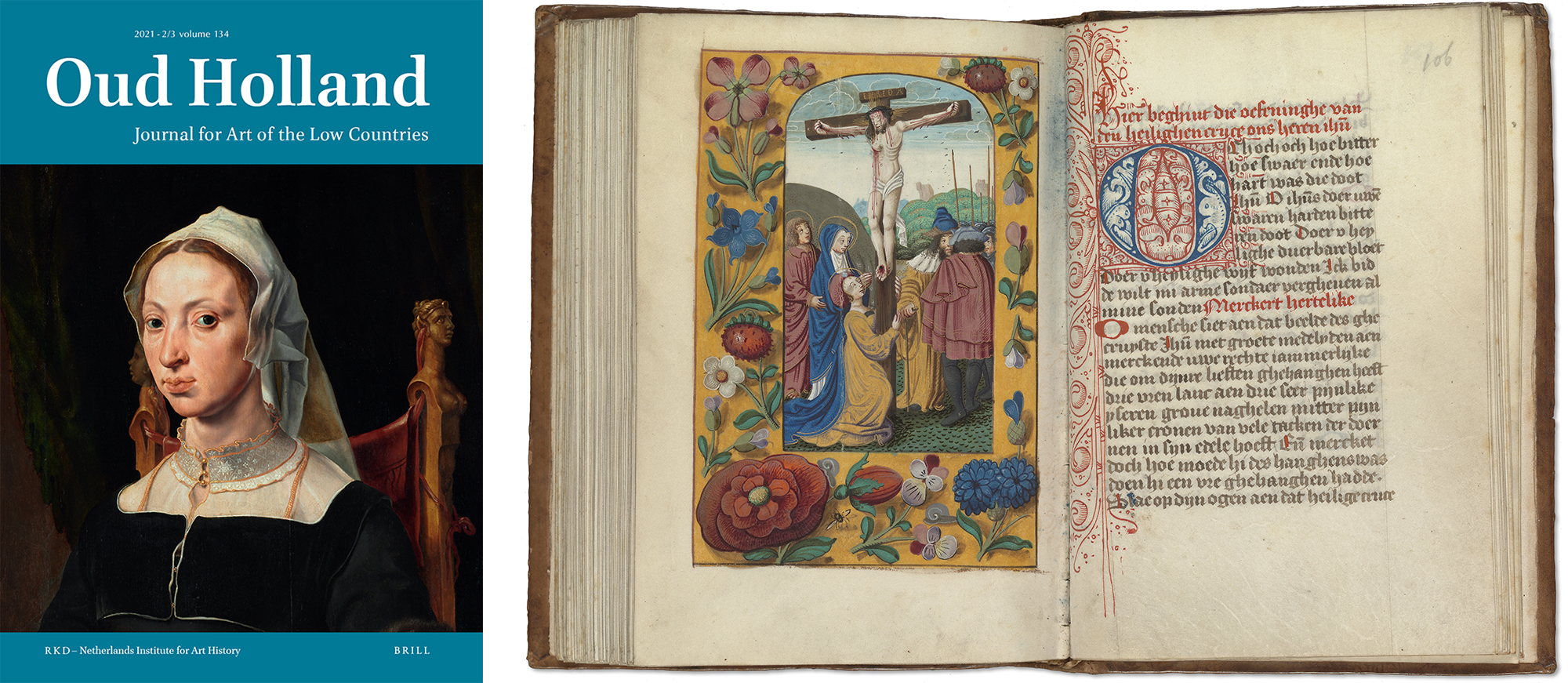

The current double issue of Oud Holland arrives just at the beginning of the new academic year. It includes thorough analyses on a wide range of topics: from medieval illuminated books to nineteenth-century religious painting in the Netherlands.

The surviving account books of the monastery of Lopsen near Leiden contain numerous payments relating to panel painting, pigments, parchment, and the writing, illumination and binding of various books. This casts doubt upon the general theory that the so-called Masters of the Suffrages were active in Lopsen. Instead, As-Vijvers proposes that the documentary records from Lopsen concerning illumination refer to pen-flourishing instead of painting.

Maarten van Heemskerck’s painting style underwent enormous development thanks to his introduction to antiquity and the Italian High Renaissance. His views on portraiture also changed considerably. Our understanding of Heemskerck’s autonomous portraiture is, however, blurred by incorrect attributions and dates. A careful analysis by Veldman is employed here to establish the authenticity of the few signed portraits that have survived, and as a means of identifying the persons depicted.

Brosens and De Prekel provide an in-depth view of Antwerp’s artistic production in the seventeenth century. From a methodological point of view, the essay demonstrates that there is great value in a combination of qualitative and quantitative readings of various sources to analyse complex social systems, such as artistic communities. Their approach proves to be instrumental in the debate on the productivity of early modern Antwerp.

Religious painting in the nineteenth-century Netherlands has been largely neglected in art historical research. The persisting misconception that art and Protestantism are irreconcilable has become an all-too easy explanation for the apparent lack of religious painting in this period. This article by Maathuis aims to understand the reception of the religious paintings of Ary Scheffer in the light of the Dutch Réveil.

The editors of Oud Holland wish you a fruitful art-historical late summer.

Anne Margreet W. As-Vijvers – Manuscript production in the monastery of St Hieronymusdal in Lopsen, near Leiden – pp. 69-100

SUMMARY

The surviving account books of the monastery of Lopsen near Leiden contain numerous payments relating to panel painting, pigments, parchment, and the writing, illumination and binding of books. They span the period from c. 1440 to 1507. This article analyses the entries that refer to writing and illumination, and discusses scribes, illuminators, and the book types mentioned. The results are compared with the corpus of extant manuscripts attributed to Leiden.

This leads to abandonment of the general theory that the so-called Masters of the Suffrages were active in Lopsen; instead, the author proposes that the documentary records from Lopsen concerning illumination refer to pen-flourishing (penwork decoration) instead of painting. The author argues that Lopsen did not produce luxury codices with painted miniatures and borders, but well-made books aptly decorated with pen-flourishing, in a South Holland style that is known as loops penwork. The extant manuscripts containing loops penwork are in line with the book types mentioned in Lopsen’s archives. Their main customers were members of churches and religious institutions: priests, monks and priors, nuns and abbesses, tertiaries and beguines, church wardens and guild masters, even though some books were made for devout lay people: educated burghers and governors of Leiden as well as family members of the Lopsen monks.

The author concludes that the results obtained by this study would merit comparison with the practices of other religious communities that are known to have produced books, and she suggests that some other monastic workshops to which ‘illumination’ has been attributed actually provided pen-flourishing. The author further concludes that different patterns of production can be found in the northern Netherlands in the fifteenth and the early sixteenth century, which invite exploration of the relationships between urban and monastic workshops in other Dutch cities, such as Delft, Haarlem, Amsterdam, Utrecht, Zwolle and Groningen.

Ilja M. Veldman – Artistic innovation in Maarten van Heemskerck’s portraits after 1537 and new identifications in the light of his social network – pp. 101-129

SUMMARY

Maarten van Heemskerck’s painting style underwent an enormous development thanks to his introduction to antiquity and the Italian High Renaissance. His views on portraiture also changed considerably. Shortly after his return from Rome, he painted three life-size portraits of Alkmaar patricians in an Italian-aristocratic style. Understanding of Heemskerck’s autonomous portraiture is, however, blurred by incorrect attributions and dates. A careful analysis of style and dates is employed here to establish the authenticity of the few autograph portraits that have survived, and as a means of identifying the persons depicted.

The identification of the Alkmaar portraits has never presented problems, because they bear family coats of arms. Heemskerck’s portraits of a woman in Antwerp and Haarlem and his portrait of a man in Rotterdam, however, were not provided with coats of arms. They are presently known by names that have been wrongly attached to the subject. Thanks to research into the painter’s social network and family ties, the portrait in Haarlem can now be identified as Heemskerck’s wife Marie Jacobsdr de Coninck, while the Rotterdam portrait appears to represent the Haarlem scholar and alderman Cornelis van Beresteyn. Heemskerk’s portrait of the Haarlem printer Jan van Zuren has been lost. The artist’s preference for portraits of his own circle of friends and relatives corresponds to the practice prior to his Italian journey: cf. the portrait of Heemskerck’s father, and that of the family of Pieter Jan Foppesz, with whom he lived for a while.

A career as a portraitist of prominent people became unlikely in the course of the 1540s. Heemskerck probably faced too much competition from both Jan van Scorel and Anthonie Moro, whose connections enabled them to become the favourite portraitists of the elite. While Heemskerck continued to demonstrate his talent in portraits of donors on altarpieces, he seems to have chosen at an early stage to apply his new spectacular style, formed in Italy, to devotional and biblical subjects and classical history. For him, as it would later be for Karel van Mander, history painting was probably the highest form of art, and the one best suited to display his imagination and compositional skills.

Koenraad Brosens & Inez De Prekel – Antwerp as a production center of paintings (1629-1719): A qualitative and quantitative analysis – pp. 130-150

SUMMARY

Since the 1990s, there has been a steady interest in Antwerp as an early modern production and marketing center of paintings. However, an in-depth view of Antwerp’s supply side in the seventeenth century is still missing. This essay addresses this lacuna by presenting an analysis of the Antwerp Guild of Saint Luke between 1629 and 1719 with a focus on the group of painters.

From a methodological point of view, the essay demonstrates that there is great value in a combination of qualitative and quantitative reading of various sources to analyse complex systems, such as artistic communities, and how they evolved through time. In so doing, it illustrates the potential of a slow computational art history approach that maximises the potential of analysis and exploration of data and data visualizations, while at the same time respecting data contexts and data issues.

Our analysis shows that, unsurprisingly, the guild and the community of painters suffered from the economic crisis that hit Antwerp after 1650 and from changes in consumer preferences that occurred in the 1680s. However, the statistics also show that the guild showed remarkable resilience, and that Antwerp remained the prime production center of Flemish painting until 1700. The robustness did not appear out of thin air, but was engineered by the board and established masters. Using the freedom offered by the organizational and regulatory framework, they machinated the number and careers of apprentice painters and founded an Academy in a successful attempt to recruit aspiring artists. This, however, is not to say that established masters favored uncontrolled growth in the cohorts of apprentices, journeymen and masters. Small workshops were and remained the norm.

While the numbers and guesstimates presented in this essay are indicative rather than absolute, the emerging patterns and trends can support two strands of future research. First, it can be instrumental in the debate on the productivity of early modern Antwerp and indeed European artists that still await fine tuning. Second, the essay can also help art historians to better understand the entrepreneurial behavior of individual art producers in seventeenth-century Antwerp, and, consequently, contemporary artistic developments.

Marieke Maathuis – An aesthetic of devotion: Ary Scheffer and the Dutch Réveil – pp. 151-168

SUMMARY

The subject of religious painting in the nineteenth-century Netherlands has been largely neglected in art historical research. The persisting misconception that art and Protestantism are irreconcilable has become an all too easy explanation for the apparent lack or scarcity of religious painting in the Protestant Netherlands in this period and a consequent disinterest in the subject. Nonetheless, religious art continued to exist in the nineteenth-century Netherlands and took on new forms which corresponded to people’s more personal experience of faith. Notwithstanding the critical and doubtful attitude towards religion that arose around this time, not everyone gave up on Christianity and its teachings. In fact, the nineteenth century witnessed a range of religious revivalist movements throughout all of Europe and America. The Netherlands saw the rise of the Réveil movement, a revivalist movement within the Dutch Reformed Church, whose protagonists largely coincided with a cultural elite including many writers, poets and art lovers. They can be linked to numerous religious artworks, especially those by the French-Dutch painter Ary Scheffer (1795-1858).

This article aims to understand the reception of the religious paintings of Ary Scheffer in the light of the Dutch Réveil. By providing a cultural context, bringing together religious, literary and artistic elements, it will become apparent how Scheffer’s paintings resonated with this specific audience. The aesthetic for religious painting that Scheffer brought forward can be characterised as strongly devotional images, in which traditional biblical narrative is consciously evoked, but rendered with minimum means. The focus on the psychological state and emotion of protagonists that comes forward resonated with the religious climate in the Netherlands at the time, focusing on piety and a personal experience of faith. Though Scheffer’s art is nowadays often regarded as too sentimental, this study helps to understand their value to the nineteenth-century religious beholder.