Dec 2024: Adriaan de Vries and Nicolaas de Roever, a 140-year-old friendship

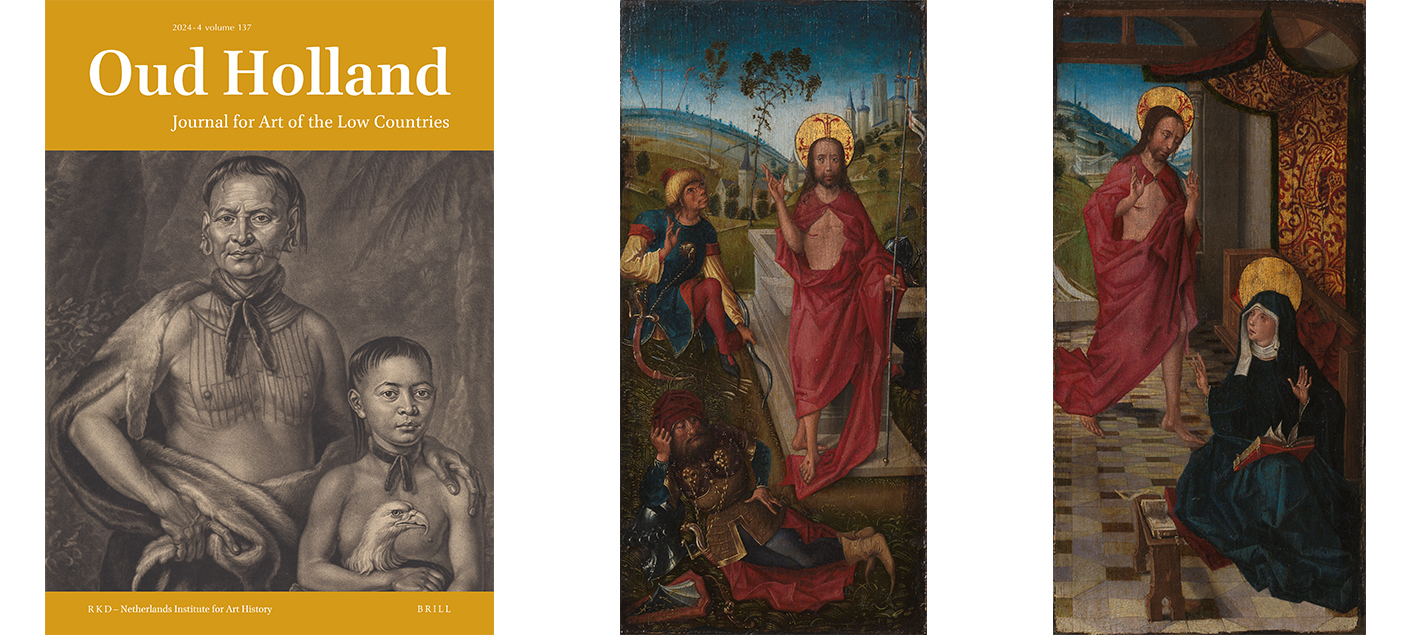

New issue: Oud Holland 137 (2024) 4

18 December 2024

One hundred and forty years ago, founder of Oud Holland, Adriaan de Vries, sent a note to his friend and fellow editor Nicolaas de Roever. The message, dated 7 February 1884, informed him that, due to fever, he would be unable to complete a Rembrandt article he was working on. De Vries died a day later, aged just 32. In this winter issue the extended editorial dives deeper in this moving relationship and the early days of Oud Holland.

Thanks to a detailed comparative study of two formerly undocumented altarpiece shutters from the last quarter of the fifteenth century, an Annunciation and four scenes from the Passion cycle, Alexandre Dimov and Didier Martens now attribute them to a member of the workshop of the so-called Master of the View of St Gudula in Brussels.

Through indepth archival research, Peter Hancox presents a thorough overview of the members of the Dutch and English Verelst family, in particular of the genre painter Pieter Verelst, and his sons Herman, Simon, John and William. Four of Herman’s children and one of Pieter's great grandchildren became portraitists in London.

Henri van de Waal, inventor of Iconclass, also worked on a little known classification system of the arts which he called 'Beeldleer' (Iconology). In his article, Charles van den Heuvel explains this system and explores its potentials to complement historical debates on iconology and for future application in digital art history.

The editors of Oud Holland support the massive protests in the Netherlands against the destructive cuts in academia, for proper education and research are the pillars of democracy. We wish you a peaceful 2025.

Editorial – Adriaan de Vries and Nicolaas de Roever: A 140-year-old friendship – pp. 141-149

SUMMARY [download article]

This special editorial pays tribute to the warm friendship between Adriaan de Vries (1851-1884) and Nicolaas de Roever (1850-1894), which lay at the foundation of Oud Holland. Friendship is, after all, indispensable to the creation of a scholarly journal and to maintaining it over time. The archival researchers left behind archives of their own, which form a rich source for the bond that existed between them.

The Oud Holland archive (kept in the RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History) takes up around six metres of shelf space and contains documents dating from 1877 to the present. While it has yet to be made available systematically and has never been properly studied, it is certainly well ordered. De Roever's share of the archive includes hundreds of letters and postcards from De Vries, the publisher Binger, authors and readers.

To mark the 140th anniversary of De Vries' death, this editorial focuses on the friendship between De Vries and De Roever, and on the engraved portrait of De Vries that De Roever commissioned in 1884. An adapted version of the resulting print opened the second volume of Oud Holland in 1884.

Alexandre Dimov & Didier Martens – The legacy of Rogier van der Weyden: A pair of altarpiece shutters by the workshop of the Master of the View of St Gudula (c. 1480-1500) – pp. 150-173

SUMMARY

This article aims to illustrate the legacy of Rogier van der Weyden (1399/1400-1464) in Brussels through two formerly undocumented altarpiece shutters from the last quarter of the fifteenth century that were auctioned in 2020. An Annunciation is depicted on the reverse of the panels, while the observe shows four scenes of the Passion: the Flagellation of Christ, the Crowning with thorns, the Resurrection of Christ, and the Christ appearing to his mother.

The central 'caisse' of this domestic retable, which was probably a carved group, is missing. The paintings can be ascribed to an artist working in Brussels, in the workshop of the Master of the View of St Gudula. A similar Passion cycle, that has been recorded on the Paris art market in 1924, can be attributed to the same workshop. In the present altarpiece shutters, the relationship between the Annunciation and Rogier's oeuvre is particularly straightforward, as the figure of the angel Gabriel appears in a similar form in a painting by one of the master's pupils. In addition, following a motif introduced by Rogier, the sceptre of Gabriel is connected with 'tenons' as if it was a real sculpture. Obvious similarities also appear when comparing the Flagellation and the Crowning with thorns with two drawings by an artist from Rogier's closest circle. Also, the composition of the Flagellation can be found in the central panel from the Prado's Triptych of the Redemption, a work that clearly relies on Rogierian models.

The works that Max Friedländer attributed to the Master of the View of St Gudula in 1926 and 1939 are characterized by differences in quality of execution and style, what scholars led to assume that the artist must have been surrounded by a workshop of several collaborators. Following the authors, one of them, the same who was responsible for two panels from a cycle of Saint Catherine, can now be convincingly assigned to the present altarpiece shutters.

Peter Hancox – The multigenerational and cross-national artist family Verelst (c. 1618-1752): The myth of Cornelius and Maria – pp. 174-200

The number of practising artists in the multigenerational Verelst family in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries has led to confusion as to their identification, partly because of the repetition of names between generations. Pieter Verelst (c. 1618-1668) worked in Dordrecht, Rotterdam, The Hague and possibly London, training several of his sons, certainly Herman (1641-1699), Simon (1644-1717?), John (1648-1679), and possibly William (1651-1702). By the mid 1660s, Pieter, Herman, Simon and John were active in the Low Countries but struggling financially. Pieter and Simon emigrated to London with John following via France. Herman worked in Venice, Ljubljana, and Vienna (where he and his family had to flee ahead of the Turkish siege of 1683) before settling into a successful career in London.

Four of Herman's children became portraitists. John (c. 1670-1734) was initially successful as a court painter but failed to maintain his position, ending in bankruptcy. Michael (c. 1675-1752) became a provincial artist in Nottingham. Lodvick (1668-1704) was also a portraitist. Adriana (c. 1683-1769) was successful with commissions from the aristocracy and landed gentry; an unsuccessful marriage deprived her of wealth but she received a generous legacy from a friend which compensated.

One of Pieter's great grandchildren, William (1704-1752), was the last of the artistic line. Like his father, John (c. 1670-1734), he had a career with some success as a portraitist with commissions from the East India Company and the Georgia Trustees as well as landed gentry, although it ended in bankruptcy.

Literature from Weyerman in 1729 onwards refers to two other artists in the family: 'Cornelius' and a female artist at first named as 'N. Verelst' or 'Mlle Verelst' but eventually named as 'Maria Verelst' by Bryan in 1816. There is no contemporary evidence for either under those names: it is argued that they are mis-namings of William (1651-1702) and Adriana respectively.

Charles van den Heuvel – Henri van de Waal's (1910-1972) unfinished Beeldleer: Exploring new potentials of an iconological classification for the history of the arts – pp. 201-236

SUMMARY

Henri van de Waal (1910-1972), well-known for his development of Iconclass, also worked on a classification system of the arts that has remained unknown to many, entitled 'Beeldleer' (Iconology).This article explores the new potentials of Beeldleer, despite its unfinished and occasionally outdated character, to complement historical debates on iconology, and for future application in digital art history.

Firstly, it will be demonstrated, using unpublished archival documents of the development of Beeldleer, why it is a necessary addition to Iconclass to fully understand Van de Waals approaches of art history in general and his views on iconography and iconology in particular. Although Iconclass certainly has classes that are relevant beyond a history of art based purely on semantic meaning using foremost figurative examples, Beeldleer has additional value. A comparison between these classification systems revealed that the publication of Beeldleer, even in the unfinished state it has remained in, would allow for much completer descriptions of non-figurative aspects of the arts, also in non-Western contexts.

Secondly, Van de Waal's contribution to iconology has merely been read through the lens of Iconclass and foremost in comparison with the views of Aby Warburg and Erwin Panofsky. Although Van de Waal admired these art historians, archival sources make clear that he put more emphasis on the role of observation to come to a theory of form. He regarded such a theory a precondition for iconology as a theory of meaning for understanding the function of the image in society. Van de Waal's Beeldleer is not only relevant for the historiography of iconology in the Low Countries but can also contribute to analyses of international debates in the history of art and media studies (in particular around 'Bildwissenschaft'). Moreover, after update of some classes, Beeldleer allows for classifying the outcomes of current analyses of the making of artworks and of global art history.

Thirdly, the article demonstrates that Beeldleer can be crucial in providing more art historical context in modeling and (pre-) classifying the outcomes of computer vision experiments. In particular, the many classes to capture formal aspects make Beeldleer very useful for such experiments in digital art history. The inclusion of many categories that refer to non-visual arts allows for linking to other classifications.

The publication of Beeldleer on the Semantic Web could be the realization of Van de Waal's 'globus iconographicus', a tool designed to map uncharted areas of iconography and iconology.