Review of: 'Van Gogh and the seasons' (2018)

February 2022

RENSKE COHEN TERVAERT

Review of: Sjraar van Heugten (ed.), Van Gogh and the seasons, Princeton [Princeton University Press] 2018

The lifelong fascination of Vincent van Gogh (1853-1890) (fig. 1) for the natural world around him has been thoroughly explored, especially throughout the past few decades. Exhibitions such as ‘Vincent van Gogh: Timeless country – modern city’, held at the Complesso Monumentale del Vittoriano in Rome during 2010-2011, as well as ‘Van Gogh and nature’ at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts, in 2015, are two examples.1 In the accompanying publications, Van Gogh’s deep appreciation for the rhythm of the seasons and the religious connotations that he attached to this, have also been touched upon. These two projects were a prelude to even more extensive research into Van Gogh’s artistic and spiritual relationship to the seasons, which has resulted in the here reviewed publication.

In 2017, Art Exhibitions Australia and the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) in Melbourne presented the exhibition ‘Van Gogh and the seasons’, curated by the Van Gogh scholar and independent curator, Sjraar van Heugten, and Dr. Ted Gott – NGV’s Senior Curator of International Art. The exhibition displayed 36 paintings and 13 drawings by the famous Dutch artist, mostly derived from the two largest collections with Van Gogh’s work: the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam and the Kröller-Müller Museum, in Otterlo. Besides works by the master himself, Japanese prints from the NGV’s collection were also included, as were a selection of European prints from the artist’s personal collection, which are today held at the Van Gogh Museum.2 It was the second, and the larger, Van Gogh exhibition that’s been organised by the NGV.3 While the exhibition itself was ‘exclusive-to-Melbourne’, the approach – the focus on Van Gogh’s fascination for the changing seasons and the cycle of life, literally and metaphorically – and its research have been preserved in an internationally available (excluding Australia and New Zealand), lavishly illustrated publication, published by Princeton University Press during 2018.4 The exhibition catalogue has a traditional layout: starting with in-depth essays by renowned scholars and followed by short entries about the works shown in the exhibition categorised per season. The texts are elaborately adorned with images, and many spreads zooming in on works, have been added. Unfortunately, the incredibly glossy paper for this generously sized book is poorly chosen. While the actual paintings and drawings are on display in anti-reflective glass, the reflection of the paper makes studying the images a challenging endeavour. The first essay ‘Vincent van Gogh and the seasons: images of nature and humanity’, was written by Sjraar van Heugten, initiator of the exhibition, and one of the authors of both the aforementioned publications on Van Gogh. His essay functions as an introduction by showing how Van Gogh’s love for nature and his spiritual temperament can be traced back to his youth and his upbringing. Following Van Gogh’s artistic path of life – from his early seasonal motifs drawn in the Borinage inspired by his greatest example Jean-Francois Millet (1814-1875) to the blossoming chestnut trees and the panoramic paintings of wheat fields surrounding Auvers in the last months of his life. He describes the artist’s many sources of inspiration, his reflections on the seasons during important moments in his life, its resonance in his oeuvre, and upon his artistic development.

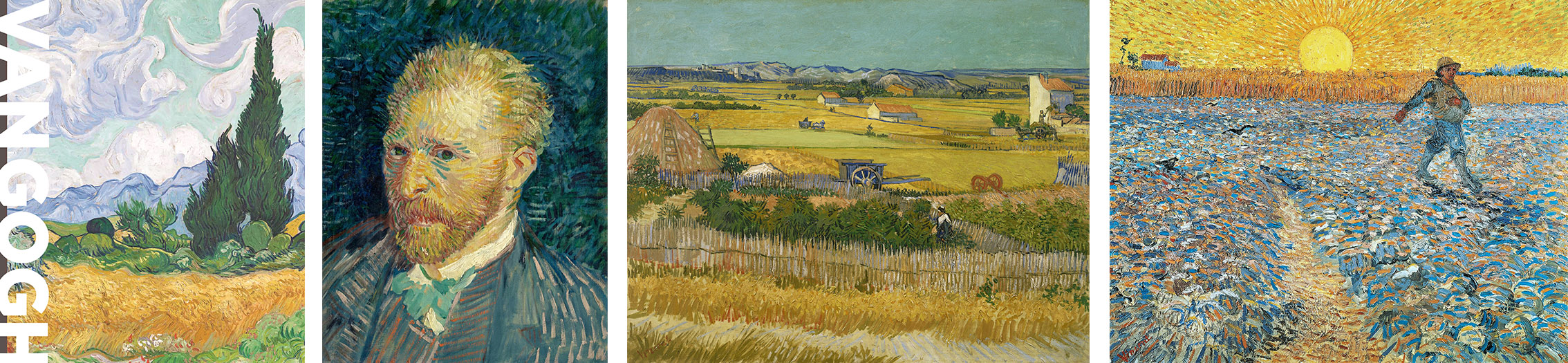

Left: cover of Van Gogh and the seasons.

Middle left: fig. 1 Vincent van Gogh, Vincent van Gogh self-portrait, 1887, oil on canvas, 44.1 x 35.1 cm., Musée d’Orsay, Paris, inv. RF 1947 28.

Middle right: fig. 2 Vincent van Gogh, The harvest, 1888, oil on canvas, 73 x 92 cm., Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, inv. s0030V1962.

Right: fig. 3 Vincent van Gogh, The sower, 1887, oil on canvas, 64.2 x 80.3 cm., Kröller-Müller, Otterlo, inv. KM 106.399.

From Van Heugten’s essay (but also from the entries in the second part of the book), it becomes apparent that Van Gogh did not only visualise the seasons by painting landscapes. Landscapes featuring the blossoming orchards in spring; the bright and burning summer sun; fields covered with a thick blanket of snow; or the orange, yellow and brown tones to capture the autumnal effects (fig. 2). The choice for specific seasonal flowers, but also the spoils of harvest, place his still lifes in this context as well. More importantly and central to the argument of this publication, is the portrayal of seasonal labour, of which field sowers are without a doubt, the most famous motif in the artist’s oeuvre (fig. 3). It is satisfying that the authors also explore less evident motives in the publication.

Van Heugten argues that Van Gogh was, to a certain extent, familiar with the artistic tradition and its symbols, as he was depicting the seasons and people engaging in seasonal work. Before starting his artistic career, he gained a thorough knowledge of the Old Masters and French, English and Dutch (academic) art, with a special interest in the painters of the Hague and Barbizon schools, through his job at the art dealership Goupil et Cie between 1869 and 1873. Not only through original paintings, but also via prints. Together with his brother Theo (1857-1891) he started a collection of graphic works containing hundreds of prints, in which seasonal themes were well represented. A special part of that collection was reserved for Japanese ukiyo-e woodcuts, which also became an exceptionally important source for the artist. It seems unsurprising that of the four seasons, motifs of spring – especially blossoming trees and gardens with peonies – dominate. Due to the pivotal role the graphics play, the Japanese prints (fig. 4) and a selection of European reproductions with seasonal subjects (fig. 5), each received special attention in the book, through short entries by, respectively, Dr. Sophie Matthiesson and Dr. Ted Gott. Both authors are also curators at the NGV.

As usual when conducting research into any topic involving Vincent van Gogh, the letters to his brother Theo are the prime source of information. Besides the cited lines that are interwoven throughout the essays – in some cases even featuring multiple times – a separate chapter has been added to the catalogue for which Van Heugten selected fragments from the correspondence, in which Van Gogh’s attitude toward the different seasons is articulated. At first sight, not all the fragments seem to be relevant, perhaps due to the missing context of the citation. However, when reading the essays in more detail these do start to make sense. The added value especially lies in the passages, in which the artist used the seasons as metaphors for the passing of time and the hardships of life. They have a poetic quality all their own that more than merits their inclusion in this book.

Van Heugten’s introduction gives a focused, but elaborate insight in the established framework of scholarly Van Gogh research on the artist’s multifaceted and evolving interest in the strong connection between humankind and nature. His essay is followed by a contribution by Professor Joan E. Greer; the heart of this publication. Her essay, ‘“To everything there is a season”: the rhythms of the year in Vincent van Gogh’s socio-religious worldview’, provides a better understanding how Van Gogh developed, “a humanitarian and Christocentric approach to understanding and representing the natural world around him and humans’ position within it.”5 The importance of religion in Van Gogh’s life was well recognised in 2017 – the year the exhibition opened, and that this publication appeared in Australia. Greer mentions numerous publications, including her own efforts, to underline the stance; furthermore, she criticises the fact that it hasn’t played a more crucial role in the discourse.6 This essay is a, quite successful attempt to establish the, much warranted 'central position’.

Left: fig. 4 Katsushika Hokusai, Poem by Tenchi Tenno, c. 1885/6, colour woodblock, 26.8 x 37.2 cm., National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, inv. 417-2.

Middle left: fig. 5 Edouard Bellenger, The sower, wood engraving, 1885, 54 x 38.1 cm, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, inv. t0228V1962.

Middle right: fig. 6 Limburg Brothers, Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry, Folio 9, verso: September, c. 1412-1416 and 1440 and c. 1485-1486, painting on vellum, 22.5 x 13.6 cm., Condé Museum, Chateau de Chantilly, Chantilly, inv. Ms.65, f.9v.

Right: fig. 7 Vincent van Gogh, Tree trunks in the grass late April 1890 Saint-Rémy, 1890, oil on canvas, 72.5 x 91.5 cm., Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, inv. KM 100.189.

The fundamentals of Van Gogh’s religious views were rooted in his spirit, from his childhood onward, with a prominent place reserved for his father, Reverend Theodorus van Gogh (1822-1885). From 1876 to 1880, following in his father’s footsteps, the young Van Gogh immersed himself in theology with the goal of becoming a minister. The earliest references to the seasons and life cannot only be found in Vincent’s letters, but also in his first Sunday sermon given on 29 October 1876 – held at the Wesleyan Methodist Church in Richmond, England. He was strongly influenced by the Amsterdam preacher Eliza Laurillard (1830-1908), who integrated images of nature and seasonal agricultural labour into his preaching. Vincent’s way of practicing religion was also in concordance with the changes within Christian theory that occurred in the last decades of the nineteenth century. These changes created an environment in which, “traditional Christian iconography could function outside of a religious framework to convey the same basic ideas, with notions of spirituality and humanitarian imperatives remaining intact.”7 A few years later Van Gogh realised that his reason to become a minister – to help other human beings – could also be reached as an artist: his art could offer solace to others. This led to the historical decision in August 1880 to devote himself fully as an artist. For his artistic practice Van Gogh found models not only in the Dutch naturalist landscape painting of the Hague School, but also in French traditional and modern landscape painting, with Jean-François Millet (1814-1875) as his greatest artistic influence.

Greer designates a special part of her argument to the historical understanding of time, its accompanying visual culture in, above all, calendars, and the heated contemporary debates between religious and secular factions, to establish an international standardised time and calendar. She enriches this subject by mentioning the mediaeval breviaries and the books of hours, with the Très Riches Heures (fig. 6) as the most famous example. Greer makes us aware that secular and religious discussions (still) resonate in the reception Van Gogh’s work and also of work by other artists, which – when acknowledged – results in ‘rich and multi-layered significations’.

Not least: Ted Gott focuses on the early reception of Van Gogh’s work in a time of artistic and cultural transition in Paris. This essay is not refined to the central theme of the book, though discusses in a broader perspective, the reception of the symbolic language and spiritual exploration in Van Gogh’s art as it’s addressed in the first two essays. In his essay, ‘Conflicts of interest: Vincent van Gogh and French symbolism’, he analyses the changing sentiment of art critics towards the work of Odilon Redon (1840-1916) and Van Gogh between 1886 and 1890, because of the emergence of Symbolism. This period coincides with Van Gogh’s French years (fig. 7): from his move to Paris in February 1886, and his first encounter with Impressionism and Neo-Impressionism that ultimately inspired him to change his palette and technique, until his death in July 1890. Symbolism, a reaction against the domination of naturalism, especially gained momentum after 1888. Van Gogh had moved to the south of France in the beginning of that year and therefore, largely missed the impact on art and art criticism of the new aesthetics brought on by notions of mysticism towards more spiritual expressions. Nevertheless, it was to have a profound effect on his persona, and the appreciation of his work. The principal actor in this sense was the art critic Albert Aurier (1865-1892). As a good friend of Émile Bernard (1868-1941), Aurier was familiar with the work of the Dutch artist. His article ‘Les Isolés: Vincent van Gogh’, published in the Mercure de France in January 1890, would lead to the scarcely refutable misconception of the artist as a genius – but also as a loner and a recluse, the latter already challenged by the artist himself during his lifetime. As has already been argued by other Van Gogh scholars as well, it coined the start of the myth as him being a genius artist.8 The essay is a welcoming – albeit not a vital – addition to the central topic of the publication. Gott ends his essay with a citation from a letter written by Theo van Gogh to Aurier after his brother’s death. In this letter Theo expresses his gratitude to the critic, who was the first to appreciate Vincent’s work: “[…] you have read these pictures, and by doing so you very clearly saw the man.”9 In a way, the scholars of this publication followed in Aurier’s footsteps. Their effort brought the cycle to explore nature and its deeply personal and religious resonance in Van Gogh’s life and work, to a temporary conclusion. However, seeds were sown and already germinated into further in-depth research, of which the recent exhibition and accompanying publication Van Gogh and the olive groves is a good example.10 This research project focused specifically on the olive grove series, produced in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence in the final year of Van Gogh’s life. Beside contextualising this work within Van Gogh’s artistic production, it explores the intensely personal and spiritual meaning that the motif held for the artist. These valuable and painstaking efforts have contributed towards a deeper, and a more multi-layered focus, on one of the most cherished, though also misunderstood, artists of our modern time.

Renske Cohen Tervaert

Curator, Kröller-Müller Museum

NOTES:

1 C. Homburg (ed.), Vincent van Gogh. Timeless country – modern city, Rome 2010; R. Kendall, S. van Heugten and C. Stolwijk, Van Gogh and nature, New Haven/London 2015.

2 For the selection of works shown in this exhibition, see the research platform Van Gogh Worldwide: 'Van Gogh and the seasons'.

3 The other exhibition ‘Van Gogh: His sources, genius and influence’, took place at the National Gallery of Art, from 19 November 1993-16 January 1994.

4 This edition published by Princeton University Press appeared a year after the identical exhibition catalogue from 2017; the latter is available in Australia and New Zealand.

5 J. Greer, ‘“To everything there is a season”: the rhythms of the year in Vincent van Gogh’s socio-religious worldview’, in S. van Heugten, Van Gogh and the seasons, Princeton 2018, p. 61.

6 Van Heugten 2018 (note 5), p. 242, n2.

7 Van Heugten 2018, p. 62.

8 For example: R. Esner, ‘Beyond Dutch. Van Gogh’s early critical reception 1890-1915’, in R. Esner and M. Schravemaker (ed.), Vincent everywhere. Van Gogh’s (inter)national identities, Amsterdam 2010, pp. 137-145.

9 T. Gott, ‘Conflicts of interest: Vincent van Gogh and French symbolism’, in Van Heugten 2018, p. 98.

10 N. Bakker and N. R. Myers (ed.), Van Gogh and the olive groves, Dallas 2021. Dallas Art Museum, Dallas, Texas: 17 October 2021-6 February 2022; Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam: 11 March-12 June 2022.

CITE AS:

Renske Cohen Tervaert, ‘Review of: Van Gogh and the seasons’, Oud Holland Reviews, February 2022.